First, let me say this: If this is your first introduction to uterine anatomy, stop and read this before you come back.

The women in my family all started their periods at the age of 13. I remember hearing the calls of my sisters from the bathroom. “Mom! It’s started.” I remember hearing about cramps and watching them pick out pads. They discussed tampons over dinner when Dad wasn’t around. So it was no concern to me when one day, there was blood on my underwear. I simply grabbed the pads and moved on. This was at the age of 12, one year before average for my family. It might have been a sign of what was coming, but I had no idea.

It seemed common enough. My period would last for about 7 days and then go away. Sometimes for a month, sometimes for two months. At its longest, it was gone for a solid three months, and then it spotted back into existence. I waited patiently for the hormones to even out.

One day, I started bleeding. It was heavy and thick. There was PMS. There were cramps. I was tired. For personal and family reasons, I rarely thought to keep track. I would mark it out some times, but I wasn’t diligent. This time, I did keep track. Something that felt like a few days passed. During these days, I would go through the largest pads I could, often three or more in a day. It didn’t stop blood from occasionally trickling down my leg. My mother said this was normal and had happened to her on many occasions. (Here’s a hint, mom: not to this degree.)

At long last, I thought to myself, “actually, it feels like forever since I started packing extra pads to school. And I’m awfully tired.” Upon looking at my calendar, I realized that it had been two solid months of heavy bleeding. My mother almost didn’t believe me. I was 13 and trying to convince her that I might be dying.

When I finally went to a doctor, we found out I was anemic from the blood loss. I also found out that I would need to make several different appointments with many types of doctors to figure out what was going on. I jumped through hoop after hoop. I took some pills that made me really angry and they didn’t help. When the doctor wanted me to try the same pills again (just to be sure, I assume), I noped out of there as fast as I could.

Finally, I found one doctor who set up a plan. That plan involved no pills, but an ultrasound. I finally had a name for this disorder: PCOS.

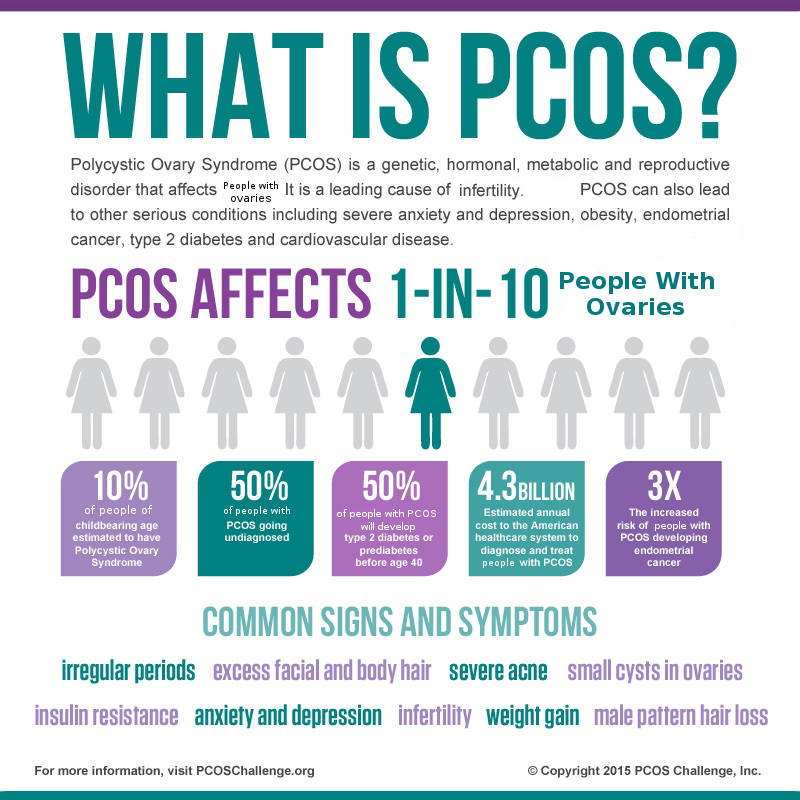

This is a common ailment among folks with vaginas. It’s called PCOS, which is short for Poly-Cystic Ovary/Ovarian Syndrome. This name is almost a misnomer because PCOS has been used in recent history as a catchall for a lot of symptoms that have nothing to do with cysts on the ovaries. However, it’s important to know that one particular set of symptoms is consistently associated with the ovaries. This list commonly falls under the diagnosis of PCOS.

The ovaries are responsible for producing hormones related to sex and reproduction primarily. In the interest of accuracy, these hormones also regulate breast growth, hair growth and acne in some cases. In the interest of humanity, folks with vaginas are not exclusively for sex and making babies. The ovaries do so much for our bodies, that I cannot overlook these things with a clean conscience.

When the ovaries are not functioning within certain parameters, negative consequences are likely to happen. Regardless of the cause, the consequences will be similar across the board. That’s why I don’t feel so strongly about the diagnosis of PCOS for problems that don’t involve cysts.

So what is PCOS?

There are three common types of PCOS:

When the ovaries fail to properly produce or drop the ovum

When the ovaries have cysts (fluid sacs attached to an organ)

When there’s a high amount of androgens (commonly known as “male hormones”) present.

These three things can all be a cause for PCOS. Some folks with vaginas have just one or two. Some folks have all three. It’s common for folks to have just the high levels of androgen and failed ova, but not actual cysts.

In many cases, PCOS causes anovulatory infertility. This simply means that infertility is caused by the lack of an ovum in the fallopian tube or uterus, as opposed to a deformation of the other organs, or in some cases, fertilized ovum being unable to attach to the uterine wall.

What are the symptoms of PCOS?

The most common symptom of PCOS is irregular periods. (Mine was truly a horror story among PCOS-havers). Other symptoms include excess body/facial hair, acne on the back and shoulders, skin changes, and others. For a full list of symptoms, I would recommend this page.

How is PCOS diagnosed?

These days, it’s very common to use no tests when diagnosing PCOS. When I was diagnosed, I was also given a hormone test (my androgen levels were the highest she’d ever seen), along with my ultrasound. However, this was years ago, and it’s ultimately not worth the work and time anymore. PCOS is common enough to diagnose by the symptoms, and it’s easier to place folks with PCOS on proper controlling meds without those tests.

Which brings us to this: How is PCOS treated?

PCOS is not treated outright. Since PCOS is lacking research and the curiosity of doctors everywhere, it is most common to treat the symptoms of PCOS, instead of treating the underlying cause of the syndrome.

With the irregular periods, birth control is the most common method. To treat the excess hair, birth control is again, the most common. Though there are other prescriptions that can be used. A drug known as Metformin is often used to help lower blood sugar (which is often raised by the presence of PCOS). Weight gain is often controlled with diet and exercise.

There have been many reported cases of PCOS being cured or extremely reduced by weight loss. However, a result of having PCOS is that it makes weight loss much harder to achieve. (This is a reminder that weight-shaming is wrong and many folks who struggle with weight, struggle for reasons they can’t control.)

What puts you at risk for PCOS?

No one knows for sure, but there is a correlation found in folks whose parents also had PCOS. Correlation is not causation, but since conditions of the body are often genetic, it would be reasonable to draw a dotted line between PCOS occurrence and genetics.

In short, PCOS is a complex condition that can have many different symptoms and levels. My storybook ending? I found some really good birth control, which helps me keep my symptoms in line. These days, I use an IUD and don’t experience bleeding at all anymore. Either way, I haven’t had blood down my legs for about a decade, and it’s a dream come true.

For other resources, see below:

https://medlineplus.gov/ency/article/000369.htm

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmedhealth/PMHT0024506/

http://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/pcos/basics/definition/con-20028841

This post was written by Indigo Wolfe. Indigo is a genderfluid, demisexual human who enjoys adult toys, adult beverages, and adult situations. They review all of these things at their blog, Indigo is an Adult. Recently, they’ve found a love for educating others on sexuality, sexual health and sex, so they are now pursuing degrees and a career to help with those passions.